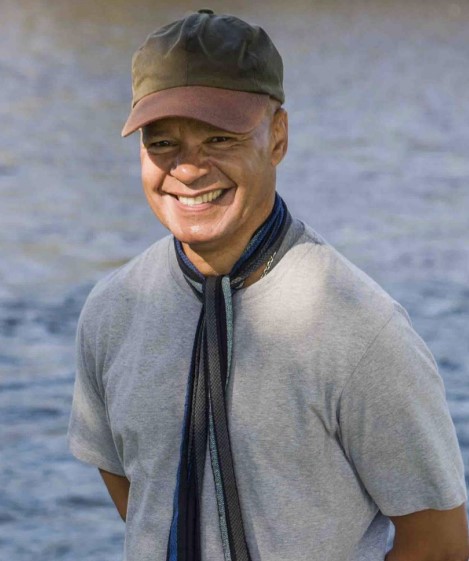

Professor hails happy childhood in orphanage: ‘I had nothing and no one. Suddenly, I did’

David Divine remembers his days at Aberlour orphanage with a keen, detailed memory but none so vividly as his last.

David said:

You never knew, you see, no notice at all. You were told if you needed to know and no one needed to know they were leaving. We would just vanish.

“You got a small suitcase. It didn’t hold much but we didn’t have much. A clean set of clothes, shorts, a shirt, pants, and that was it. I had my piggy bank too. I loved putting pennies in and counting them in bed at night.

“It seemed like such treasure but was really nothing at all.

A photograph of the same, battered, brown case features on the cover of Aberlour Narratives of Success, a book written by Divine almost half a century after leaving the Highlands in 1964, aged 11, for less happy years with a foster family in Midlothian.

Part memoir, social history, and a moving, powerful testament to the resilience of children, the book recounts the history of the orphanage before charting the lives of some of the boys and girls after they left Speyside.

Divine, who went onto university before successful careers in social work and academia on both sides of the Atlantic, said he has never cried so much as when researching the book and understanding how Aberlour had given others, like him, the tools to build a life and find happiness.

He said:

We were very damaged but many of us went on to have successful lives, whatever that meant for each of us.

“One of the men I spoke to measured success in his garden, not in degrees and books and big jobs but in caring for plants and watching them grow.

“That struck me. It was a lesson for me. It’s about what is in your heart, what makes you feel good about yourself and, speaking only for myself, I left Aberlour with the capabilities to identify that and drive towards it.

Divine, who arrived at the orphanage at 18 months and spent almost ten years there, one of 6850 children to live there from 1875 until it closed in 1967. He says he found a family there.

He was placed in care after being born in 1953 in Edinburgh. His mother white, his father a black American airman once stationed nearby.

“I was a scandal, a horror for my mother’s family. They ousted her and they ousted me.

“I literally had nothing, I literally had no one, and Aberlour gave me something and somebody.

“It gave me food, shelter and affection. It gave me a family and I was happy there.

“I felt loved there, nurtured, and I’d never, ever had that before.

“In some ways, they were the happiest days of my life.

Divine believes his recollection of life at the orphanage are clear-eyed not rose-tinted and acknowledges other children may not share the same, largely happy, memories.

There is no doubt there could be sadness and bleakness and, we now know, incidents of abuse but that was not my experience.

“All I can say is that was not my experience and that’s not what I found at Aberlour.

“What I found there was the only place in the first 20 years of my life where I actually felt nurtured, loved, cared for and valued.

“For me it bordered on paradise because of the staff, who clearly cared for me, like my house mother, Auntie Phyllis, the other children, the surroundings.

After studying at Edinburgh University, Divine launched a successful career in social work becoming Britain's first Black social services director in 1987, in the London borough of Brent before joining The Central Council for Education and Training in Social Work.

He left Britain for a professorship at a Canadian university years ago, and now lives in Nova Scotia, but has lost none of his reforming zeal or passion to improve the life chances of children in need.

Aberlour orphanage closed in 1967 as residential care homes became smaller, less institutional, and, whenever possible, children were kept with their families.

Divine said the change in direction improved care for many children but their fundamental needs remained unchanged.

He said:

The idea that closing these big homes and moving care to smaller units would somehow remove all the challenges was wishful thinking.

“The same challenges remain, and good, caring staff are still the key.

“The positive stories told by people once cared for in these big homes, people like me, have undoubtedly been overshadowed by the stereotypical idea of them as these Dickensian institutions mired in abuse and misery.

“The danger is that we don’t look back with clear eyes and lose the chance to learn some very valuable lessons on how to build new, loving families for children in care.

“Many of those lessons could be learned in the orphanage.

Divine understands why such large institutions were closed but insists size matters less than quality of staff and insists a nurturing, ad hoc family in care is better than none or parents incapable of delivering love and support.

He said:

I would absolutely say that I found family at Aberlour, I found a home where I had none.

“In many of the most important ways, it still feels like home.

“The size and condition of any residential home matters but it does not matter as much as having staff who are on a mission to offer the children there every possible support.

“It does not matter as much as having care providers who are driven by helping those children to identify what a successful life might look like for them and help get them ready for it.”

“We need to be having those conversations to find out what children value, what they want to achieve and how.”

“There must be a partnership, between the child and adult carer, and that demands well paid, well trained, well led, skilled and committed staff.

He admits, however, those were conversations that did not happen at the orphanage.

He said:

No, we were essentially told what our futures would be. We had no part to play and did as we were told.

“However, we were chronologically young but, because of our experience, ancient with wisdom and knowledge.

“We needed all that wisdom to navigate through life because we had nothing. Without that ability to navigate and the knowledge of where we needed to be, we would have got nowhere.

“It’s about survival but people don’t like that kind of language.

“There must be more to life than survival, they’ll say, but when you have nothing and no one, survival skills are what matter. How will I, with no one, navigate through life?

“Things like education and good jobs are part of that, but are these the things that have value for children? What do they believe would be a valuable life?

“We need to talk to the children, discuss their ideas of a successful, productive life and, most importantly, help convince them it can be achieved.

Divine visited Scotland, and Aberlour, regularly before Covid and plans to return for events marking the 150th anniversary of the charity, named after the town, where he spent a happy childhood.

Speaking from his home in Canada, he said:

At 71, I have nine grandchildren, three loving adult children and a partner, and we all love each other and help each other, care for one another.

“I know how fortunate I am to have someone who cares for me, and children who love me.

“I am very grateful.

This article was written as part of the 'We are family' special edition supplement with the Sunday Post.